I’m not one of the those people who possesses the natural ability to learn another language.

We lived in Austria for seven years back in the late 80s-early 90s. I’d taken two years of German in high school and two years at the university level and I still embarrassed myself on a fairly regular basis while shopping or chatting with neighbors.

Our first tutor, Gabi, assigned homework each time we met. We were to read, write and watch the “telly”. Preferably kids’ shows, but at that time the night time soap opera, Dallas, was popular in Austria. My husband and I watched it faithfully. Not because we liked it, but because it was great language practice. We were learning our new language in the same way in which small children learn their native language; by hearing complete sentences in their proper context and with full-on visual support.

I would listen and watch closely with my notebook and pen. When I heard a complete sentence that made sense, I wrote it down. And then I practiced saying it aloud over and over again.

That’s how I learned to speak German. It’s also how I learned to read German.

In the introduction to this six-part series, I talk about the critical components of teaching reading. Oral language is at the top of the list.

Often we forget about the importance of oral language for our emerging readers. We can’t afford to neglect the intentional, daily, meaningful language learning for our youngest students (and I might add, for any of our students who are learning English as a second language).

In the article, The Essentials of Early Literacy Instruction, the authors begin the list of prerequisite skills for proficiency in reading with what they call rich teacher talk.

Rich Teacher Talk

Engage children in rich conversations in large group, small group, and one-to-one settings. When talking with children:

- use rare words—words that children are unlikely to encounter in everyday conversations.

- extend children’s comments into more descriptive, grammatically mature statements,

- discuss cognitively challenging content—topics that are not immediately present, that involve knowledge about the world,

- listen and respond to what children have to say. (Roskos, Christie, and Richgels 2003)

Notice that Roskos, Christie, and Richgels chose to place oral language development at the top of their “essentials.”

Classrooms should be full of lively, engaging conversation. Please don’t misunderstand the importance of some teacher talk. I’m not suggesting that teachers and support staff monopolize the conversation every day in the classroom. What I am suggesting, and research makes it clear, is that teacher talk springs from listening, and responding in ways that enhance students’ understanding and use of the English language.

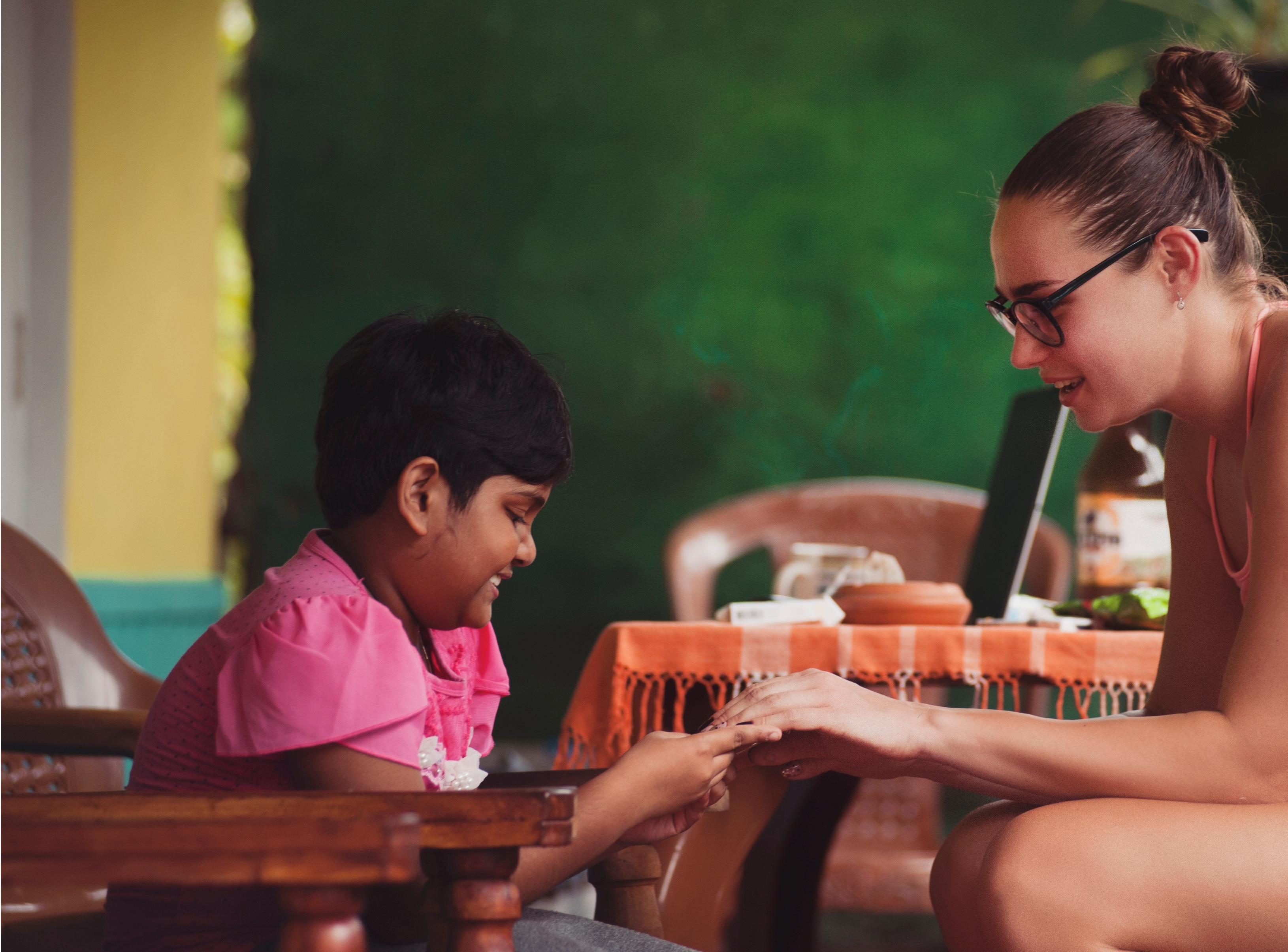

The best type of talk in the classroom involves a beautiful back and forth characterized by taking turns both listening closely and then responding. Once again, from The Essentials of Early Literacy Instruction:

“These extended conversations help children learn how to use language and understand the meaning of new words they encounter listening to other people or in reading books. They also often involve different kinds of sentences—questions and statements—and may include adjectives and adverbs that modify the words in children’s original statements, modeling richer descriptive language. For example, a child may start a conversation by showing the adult a just-completed drawing–

Child: “Look, it’s me in the garden with my Grandma.”

Teacher: (builds on the child’s statement and asks a question that encourages the child to continue), “Yes, I see. Your grandmother is holding something in her hand. What is it?”

Child: “It’s carrots. We planted the seeds together. Grandma told me how to put the seeds in the dirt, but not touching each other.”

Teacher: (asks a question that encourages the child to use language to express an abstract thought) “What would happen if the seeds did touch each other when you planted them?”

The task of building children’s oral language might seem so easy and commonplace that it need not be included as a priority in the foundations of reading instruction. It should be made quite clear that talking to children is vastly different from talking with children. When I taught early elementary grades (including kindergarten) some years ago, I had to be intentional about including language opportunities other than giving directions or intervening for the purpose of classroom management.

Teachers talk at and to kids all day long, but do they also talk with kids?

In our classrooms, we must plan intentional time for talk. Make sure to provide a variety of talking “events” in order to maximize the power of oral language learning.

Try organizing your school day so that kids have lots of time for:

- Sharing personal anecdotes

- Talking about new ideas and new information they’re learning

- Hearing adults model more complex vocabulary rich talk (read-alouds are perfect for this–more about that in Part Two)

- Retelling familiar or new stories

- Conversing with and listening to other students for extended periods of time

One of the most powerful moves we can make as educators is to capture students’ language either in print, picture or film. Spend time eavesdropping on the kid talk in your room. Video the conversations and play them back for your own learning (this helps drive your intentional teacher talk and oral language instruction) and take time to share with kids.

They love hearing themselves and each other. You can use it as a “notice and name” opportunity. Name parts of speech, conventions of language and even civil discourse. “Did you see how Whitney asked if she could help Luke when he was frustrated that they were having a hard time sharing?”

When my young students came in first thing in the morning and wanted to tell me about their time away from our class—in great detail and at inopportune times, I had sentence strips handy in several places in the classroom and I made a quick note to capture their story so it could be shared later. When we had time, I invited the student to relate to the class what had happened and I wrote down more excerpts as they talked. Those “share” moments were posted on a bulletin board and became a popular stop when students “read the room”.

Kids are so technology savvy these days that they could videotape themselves and others. Some teachers have learned to leverage the power of Voxer and Seesaw for learning purposes in the classroom, and I’m sure there are many other resources that could be used to enhance oral language learning.

When we take the time to expose kids to new words, expressions and powerful vocabulary, we help them understand concepts in spoken words, sentences and phrases. This exposure serves students well in building their own repertoire of words and spoken conventions that they can use when speaking and ultimately leads them to discover meaning in print.